Given names have, similarly to other proper names, two main features distinguishing them from common nouns (see Nübling et al. 2012): they express “Monoreferenz” (a name refers to one and only person in the relevant context). They also express “Direktreferenz” (the reference is direct in the sense that the phonological or graphical substance of the name identifies the person without considering its meaning). “Monoreferenz” is relevant for the research questions in the present article as definiteness is inherent in given names, hence, it does not require a specific marker. Therefore, in Standard German and Italian, given names are usually used without article (see [1b] and [2b]). The use of the definite article in standard languages is, however, not excluded but very restricted. In any case, the definitive article, if present, does not express definiteness but has other functions. Consequently, the definite article in front of given names is also called “expletive article”.

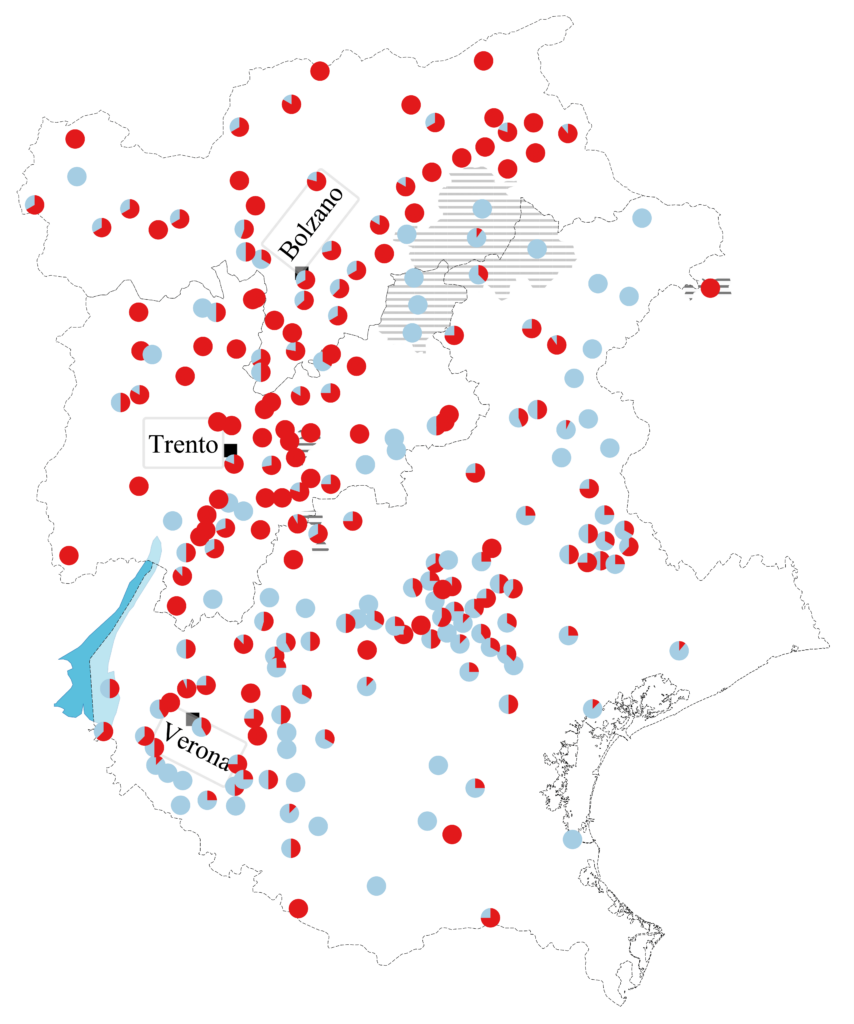

Examples (1a) and (2a) are taken from the VinKo corpus (Rabanus et al. 2023). In the VinKo project (‘Varietà in contatto’, ‘Varieties in Contact‘), the variants of the same linguistic variables for all dialects and minority languages present in the Italian regions of Trentino-South Tyrol and Veneto (belonging to either the Germanic or the Romance language group) were collected in crowdsourcing mode. In the analysis of given names and expletive articles, the dialect translations of the 28 sentences in the questionnaire, which feature given names, were considered. As of 31st December 2021, deadline of this study, informants from 229 locations had participated for an amount of 4,735 sentences with given names: 698 for Tyrolean, 104 for German-speaking minorities including Mòcheno, Cimbrian and Saurano, 226 for Ladin varieties, 676 for Trentino-Lombard and Trentino-Venetan varieties (in the Trentino region) as well as 3,031 for Venetan varieties (in the Veneto region).

The gender of the person, to which the name refers, is the most studied variable for the expletive article distribution. Two recent projects focus on this variable using Internet-crowdsourcing methods for colloquial German and Italian. The maps based on the third enquiry of the Atlante della Lingua Italiana Quotidiana (ALIQUOT, “Atlas of Everyday Italian”) underline clear differences depending on the person’s gender. The use of expletive articles with male names (il Luca, l’Antonio, il Michele) is documented in the area of Western and Alpine Lombard and, less often, in the Eastern-Lombard, as well as in the area of investigation of the VinKo project. As far as Southern Italy is concerned, there are some traces of article use with male names only in the Salento region. The region in which expletive articles are used with female names (la Sara, la Martina, la Valentina) is much bigger and includes the whole Italian-Romance area in Northern-Italy, Tuscany and Salento. The maps of the 9th enquiry of the Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache (AdA, “Atlas of Colloquial German”) show a geographical mirror image of the Italian situation. The expletive article is, in fact, commonly used in front of given names in the south of the German-speaking area, approximately south of the line Cologne-Dresden. AdA’s maps are not differentiated for gender, but based on Alber and Rabanus’ (2011) hierarchy of animacy, we expect a higher percentage of constructions with an article for the male gender in German varieties.